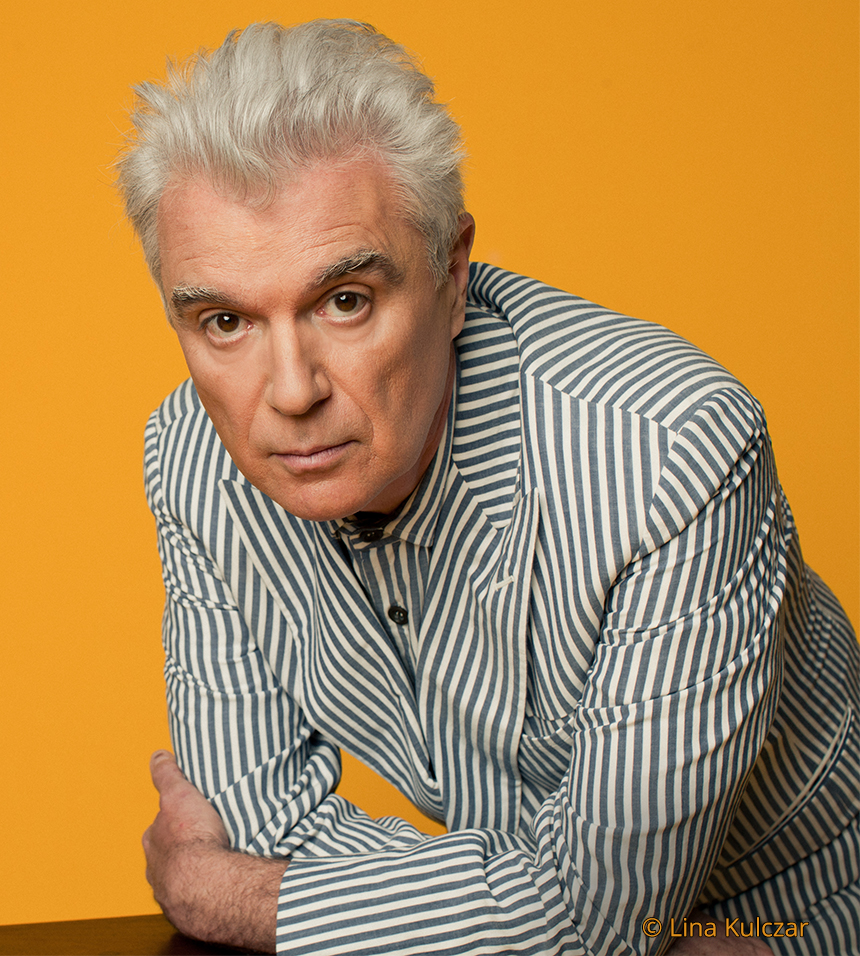

David Byrne

The Talking Heads are one of the most intriguing and influential bands in music. They have combined stark arrangements, feverishly pounding beats and hysterical lyrics to capture an audience that has outgrown the avant-garde fringe--and, surprisingly, have had hit singles from their seventh LP, "Little Creatures." Last year's Talking Heads film and sound-track LP "Stop Making Sense" were also critical and commercial smashes. The ringleader in all the fine madness is 33-year-old David Byrne, singer, songwriter and guitarist, who, solo, has also scored a Twyla Tharp dance, sections of an opera, has collaborated with Brian Eno on an album rooted in African rhythms and produced bands such as B-52's.

1.

Playboy: You're our candidate for most unlikely rock star. Are you surprised to be doing what you're doing?

Byrne: Yeah, I have to pinch myself. The most amazing part is that you can do whatever you like. That could drive you crazy. You have all these opportunities and not enough time to do them all. And there are responsibilities that come with it in all sorts of ways. If I do a video, I feel it shouldn't be too expensive, or there should be value for the money--that sort of thing. And it should express something worth while, even if I fail. But still, I can pretty much express myself any way I like. I'm exaggerating some--you can do whatever you want within what seems reasonable.

2.

Playboy: The success of Stop Making Sense and your videos has made you known to a huge audience. Has that affected you?

Byrne: The effect has been minimal. I pretty much always shave before I go out now; that's about it. Otherwise, as long as I look presentable, which is really childish, I don't mind being seen at the supermarket buying toilet paper.

3.

Playboy: Explain the magic of Stop Making Sense--which has been acknowledged as the best rock-performance film yet.

Byrne: We originally were going to use weird stage lights and stuff--it would have been controlled and perfect. But then I realized that it would lose the energy of the performance that way. In the end, we got a tasteful, or sympathetic, reporting of what was there. We went backward. Instead of using all the latest tricks and gimmicks, we opted for a really conservative approach. Really, nothing happened that didn't happen in front of your eyes. Maybe that's why it communicates to people--because it has that kind of honesty.

4.

Playboy: Who is your tailor, anyway? That suit you wear in the film is a little large, isn't it?

Byrne: The belt is somewhere around a size 58 or 60. I don't know what size the suit is, but the idea was that I wanted to be a big Mr. Man. He really is someone else. I transform myself. I almost adopt a different character when I'm singing. That's performance. When I saw myself slip out of character--when this guy was stumbling around, looking for a microphone or something--I recognized myself.

5.

Playboy: You're directing True Stories; why did you decide to go into film making?

Byrne: A big part of my background is in the visual arts. And the idea of this film was to design something that would give me an outlet for that. There's a gap between the way music is being treated on MTV or in Flashdance and the way it's done on stage in Broadway musicals. I'm trying to find that place. So the film will be a musical portrait of a town. It will be a sort of musical documentary--only more stylized. The word documentary is supposed to be box-office death.

6.

Playboy: But you've had relative commercial success with concepts that were supposed to be box-office death. How have you succeeded where others have failed?

Byrne: It's possible to do some things that are... a little unusual and still be accessible to a fairly broad public. The public is underestimated, pandered to. You don't have to pretend that people are stupid and you don't have to pretend that you are smarter than your audience. You do what interests you. That's all you can do.

7.

Playboy: The New York Times called you the "thinking man's rock star." Isn't rock 'n' roll antithetical to the life of the mind?

Byrne: I don't get too hung up on the words. The sounds of the words have as much meaning as their literal sense. But intelligent lyrics and rock 'n' roll don't have to be antithetical. Rock 'n' roll lost its innocence in the Sixties. Once Rolling Stone appeared, it was ruined right there. But even simple rock 'n' roll has that kind of intellectual awareness, or maybe just smarts. The Rolling Stones or John Fogerty--who I think of as playing basic rock 'n' roll--have something else in the music.

8.

Playboy: How important is it to you that your audience understand what you are trying to say?

Byrne: I don't know yet. I want the meaning to be in there but not specified. I do have an idea about the meaning of my song. If enough people come back to me and think it's about something completely different from what I intended, then the song wasn't very well crafted, because nobody got it. Quite a number of people thought that in Once in a Lifetime, I was trying to make fun of suburban middle-class life. But I was trying to write from the point of view of these people suddenly opening their eyes and realizing where they were. They were shocked by it and wanted to know how they got there. I juxtaposed that with a sense of surrender and relief, as if they were saying, "It's all right, even if it's a little absurd on the surface." Writing songs is a process of letting your own consciousness run loose and then reining it in. You spew out a bunch of phrases and words, almost at random. Then you have to be kind of schizophrenic about it and go, "OK, let's shape this stuff up and push it together and make a song out of it. Make a verse here. Make this rhyme with the other one." Pure emotion is sitting there like a blob and you have to whip it into shape.

9.

Playboy: How do you feel about clubs full of people dancing to your song about a psycho killer?

Byrne: I like that. It's sort of sneaky. I like that idea of the body accepting something before the mind does. I'm assuming that some of the people who listen just to the music might say (concluded on page 172)David Byrne(continued from page 99) later on, "Hey, what was that song about?" They might see the irony in it or whatever. Or they might not, which is all right, too.

10.

Playboy: What's the history of Psycho Killer?

Byrne: It was the first song I ever wrote. I had been listening to some Alice Cooper songs at the time--years ago--and I liked some of them. I wondered if you took those overly dramatic subjects and, in a sensitive way, wrote from inside the person's mind, would it work? It became a rock song, though it was intended as a ballad. It's fascinating to explore society's aberrations. Those things are in everybody; they just have gotten out of proportion for some people. I read a series of interviews with hijackers. That helped a lot, because some of them seemed to be doing it on a whim and others seemed to have a mission.

11.

Playboy: What kinds of things are in your library?

Byrne: Gosh. It changes a lot. Right now, it's all kinds of research. There's a book on film making. There's The Sanctified Church, by Zora Neale Hurston, a black writer. Part of it is about black spiritualists in the early part of the century--healers and witch doctors. Also photo books. Books about architecture. A couple of books by Gertrude Stein.

12.

[A] Playboy: What do you watch on TV? Would you describe yourself as a consumer of pop culture? And what do you do for fun?

Byrne: I hardly watch TV at all. I've been watching those documentaries on China. I listen to music, though I have to turn it off before I can start working, because it's distracting. The other day, I bought a couple of records: some African pop records, a George Jones record and one tango record. It's a real mishmash of stuff. I got a Gospel record--the Golden Gate Quartet, one of the original Gospel vocal groups from the late Thirties. Great stuff. As far as going out to relax, I went to a museum in Pasadena the other day and went to a Mexican restaurant for lunch and had some beer and then went to see Prizzi's Honor, which I liked a lot.

13.

Playboy: Can you turn the muse on or does it come on its own?

Byrne: It can definitely be turned off, but I don't know if it can be turned on. I try to turn it on by reading a page or two of Gertrude Stein, for instance, which puts me in a trancelike state. I get to the typewriter and start writing. Sometimes that opens up my subconscious. That's a nice feeling when it happens.

14.

Playboy: If you were to plan an ideal dinner party, whom would you invite?

Byrne: That's a great question. Hmmm. I'd want to invite people who might disagree; people who might never come in contact with one another, but once they meet, might really like one another.

15.

Playboy: Your songs are different in how unlike each other they are--Creatures of Love is a slightly twisted country-and-western song; And She Was is a tuneful little number about levitation; Girlfriend Is Better has the line in it, "I got a girlfriend with bows in her hair; and nothing is better than that." Care to defend your sarcasm?

Byrne: Oh, there might have been a little bit of sarcasm in the verses of that last song you mentioned, but not in the choruses. I meant it to be genuinely enthusiastic. With Little Creatures, I wanted to write stuff that gave you the feeling that you had heard the song before. Also, I've seen a lot of kids lately. They're everywhere. I played with [Talking Heads] Tina [Weymouth] and Chris [Frantz]'s kid, Robin, when we were on tour. I'm proud of that song, because it's goofy and creepy but sentimental at the same time. And She Was is just about a girl who discovered she could float and have a really good time doing it. I've heard people can do it. But I'm afraid if I were ever really successful in getting across exactly what was intended, my songs would be really boring and nobody would be interested anymore. Maybe the fact that I fail in my intentions keeps things moving on.

16.

Playboy: Some rock musicians--John Lennon and David Bowie, to name two--attended art school. So did you. Why?

Byrne: It's different in England, because the schools are free, so you could go to art school and loaf. I just knew that I was interested in doing something creative. In art school, you don't have to go through four years of training before you get to the good stuff. I was wrong a bit, but to some extent, it was cool.

17.

Playboy: Were your parents nervous about your going to art school--did they try to steer you into accounting or law? Are they proud of you now?

Byrne: They were very tolerant. More than anything else, they weren't discouraging. Once, they told me that the competition might be stiff, but that's all. It never came up again. Are they proud of me? We haven't talked about it, but I think so.

18.

Playboy: Describe your early artwork.

Byrne: Oh, there were all kinds of things: questionnaires, lists, Polaroids of flying saucers. One list was a quiz with multiple-choice questions. I remember one question about television programs: The best television programs are: (A) 30 seconds long, (B) five hours long. Those were the only choices. But that said something about the meaning of television: either short bursts of information or treating television as a surveillance medium--like the moon shots, where it's on constantly.

19.

Playboy: Which contemporary artists interest you? What's on your walls at home?

Byrne: I have things, but I don't put them on the walls. I sometimes lean them against the wall, and then I stack them away and pull a few out every once in a while. If you stick them on the walls, you wear them out; you suck the inspiration out of them. The artists I have are mostly unknown: They're considered "outsider artists," people who are schizophrenics, some of them are hospitalized, some are people who produce work on their own with total disregard for the art market. The guy who did our record cover, the Reverend Howard Finster, is one. I have a couple of small paintings by him. I'm not saying he's crazy. These are honest visions that people have, and that's what attracted me to them--their honesty. My tastes have changed, because when I thought that my ambitions were to be an artist, then I became real vicious about what I liked and what I didn't. I was in competition with all these people. I still produce visual art on my own, but I'm not in competition, so I can enjoy much more than I used to.

20.

Playboy: You were raised in Baltimore. What does someone who comes from there call himself?

Byrne: A Baltimoron. Really. My parents live in the suburbs now. They're retired and are having a great time. I'm jealous. I was apprehensive that they'd retire and have nothing to do, go nuts, immediately turn senile and watch soap operas. They're not. I visit twice a year.

It's fascinating to explore society's aberrations. I read a series of interviews with hijackers."